Introduction to Hadrian's Villa

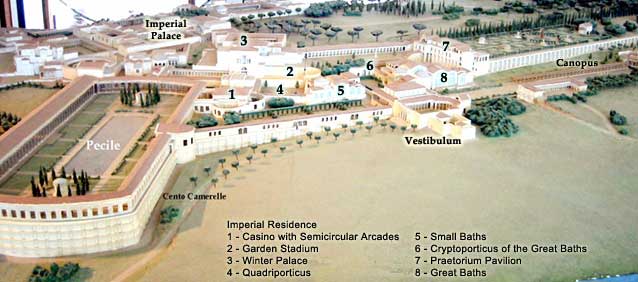

Representation of Hadrian's Villa site maps

Image by: Luis Vidal

Hadrian's Villa or Villa Adriana is situated on a small plain extending on the slopes of the Tiburine Hills. Its location is south-east of Tivoli, a town 28 km from Rome accessed in those times by the Via Tiburtina and the Aniene river, a tributary of the Tiber river. The site chosen for the Imperial residence is said to have been occupied by a smaller villa in the Republican age, owned by the family of Hadrian's wife (1). The existing structure was use in the subsequent renovations and enlargements that Hadrian order in the site around 117 AD. The ending of this enormous building project is debated, however one can say that in terms of land size, the villa spread across an area twice that of Pompeii.

Composed of over 30 buildings, the villa was created with the purpose of being Hadrian's retreat from Rome. Parts of the complex were named after well-known buildings and palaces that the emperor had visited on his travels around the empire. For example, the Canopus is a representation of the resort next to Alexandria of the same name. The recreation or association of famous buildings was very common among wealthy Romans, as it was a way of displaying culture and knowledge. One can see this in Marcus Tullius Cicero's villa in Tusculum where the buildings called Lyceum and Academia, refer to the famous philosophical schools of ancient Greece (5).

Among other distinctions, it is the greatest example of an Alexandrian garden and possibly one of the most spectacular Roman gardens. Sir Banister Fletcher depicts the gardens when he wrote in History of Architecture: "Walking around it today, it is still possible to experience something of the variety of architectural forms and settings, and the skillful way in which Hadrian and his architect have contrived the meetings of the axes, the surprises that await the turning of a corner, and the vistas that open to view" (2).

The villa is a true testament to the building prowess of the Romans due to its complexity. The site is an array of distinctive architectural creations where one can distinguish in the domes and shapes of buildings. These elements are in no way intended to follow symmetry as they are believe to have followed the shape of the rugged terrain around the villa. It is a major achievement of Western art due to its novel forms, planning and the visual and allusive invention. In antiquity, the villa use to posses many colorful mosaics and precious marbles, however, after years of treasure hunting and removal of them, only black an white mosaics remain in the site (5). Although the architect is unknown, it is said that Hadrian had a direct intervention in the design of the villa.

The complex spans an area of about 120 hectares. The central part of the palace was a traditionally structured villa that included a garden with an elongated fountain (Pecile) and view to the valley. It is surrounded by the Greek and Latin library, the main residential parts of the palace and farther away, the Golden Court. The Hospitalia or guestrooms were in the northeast side of the imperial palace. To the west, we have the Canupus and the bath with a couple of administrative buildings like the Praetoeium Pavilion. All this buildings where connected by corridors and/ or underground passages which are believe to be intended for the servants inn order to not disturb official functions in the ground levels (3).

Representation of the West-side of Hadrian's Villa

Image from: villa-adriana.net

There are several theories about its location. First, Tivoli provided the adequate supply for the construction materials needed to undertake such an ample project. For example, the renowned travertine quarries of Tivoli and the supplies of tufa, pozzolona and lime for production of cement help in the subsequent statues and foundations planned. The villa's plans called for the creation of lots of pools, baths and gardens which need a steady supply of water to maintain. This problem was solve in Tivoli by its abundant water resources that provide the water for four aqueducts leading to Rome (3). After Hadrian's questionable rise to power and his lack of popularity, the secluded location of the villa served as a shield from the criticism and the aristocrats, at the same time, it served his desire to stay away from Rome (3).

View of Geographical location of villa

Image courtesy of: Luis Vidal

WHY ERECT A VILLA?

After the conquest of Greece, the Romans were attracted to the luxury and beauty of the Hellenistic art. Roman of wealth and/or rank started to copy Hellenistic palaces and ended with a passion for villas (5). Therefore, they erected and own large country villas during the late republic and early empire. For example, Cicero, a writer who is clearly not close to being among the wealthiest of Roman, is said to have had eight villas. A closer link to Hadrian are the Julio-Claudians who built many villas. Augustus and Tiberius had villas atop the cliffs of Capri. Tiberius actually ruled the Roman Empire for most of his reign at this villa. These imperial villas started to grow in size and architectural complexity with the emperor Nero. The Domus Aurea, Nero's grandiose palace-estate in Rome, covered much of the Palatine, Caelian and Oppian hills with the valleys in between them. Suetonius describes its as having: " a pond like the sea [where the Coloseum now stands] surrounded with buildings to represent cities, besides tracts of country..." (4).

Nero's Domus Aurea villa in Rome

image by: Luis Vidal

Hadrian's predecessor, Trajan, had a villa in Citavecchia that Pliny referred to as: " a beautiful villa overlooking the sea, surrounded by the greenest of fields" (4). The luxury villa in the background of a large estates became a status symbol and a requirement for emperors in the time of Hadrian (5). Thus, one can see how the history of villas with the previous emperors and with the aristocrats would serve as motivators for Hadrian to build his impressive villa.

THE VILLA AFTER HADRIAN

After Hadrian's death, Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius continued using the villa. Wall paintings dating from the reign of Septimus Serverus show the villa was used in the early third century. Constantine was the last emperor to "use" the villa by taking work of art and other valuables. After Constantine, the villa fell into ruin and abandonment. Like many Roman monuments, in late antiquity, the site was reprieved of its treasures by different people, which explains why some statues from the villa are found in private collections, museums or have disappeared (3). First, the Barbarians of Totila sacked the site then the city and bishop of Tivoli use it as a quarry. In the XVII century, it was excavated continuously and the treasures found would end up in the private collections of Cardinals and Popes. Cardinal Ippolito II d'Este, the governor of Tivoli in the middle of the XVI century, ordered the redesign of Villa d'Este, which incurred the excavation and search for statues and other objects from the ruins of the Hadrian's Villa to be used in the decoration of Villa d'Este (5). This cycle of excavations and extraction of treasures from the site continued until the late 19th century, after the unification of Italy. Since the unification, the government took control of the site and allowed for national and international archeological groups to uncover and restore what we see today in the Hadrian's Villa. It has been named a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

View of some current remains at Hadrian's Villa

Image courtesy of: Luis Vidal

FOOTNOTES:

(1) Morselli, Chiara, "Guide with Reconstructions of Villa Adriana and Villa d'Este", Roma: Vision s.r.l, 1995

(2) "Hadrian's Villa", Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, Inc, 2006 <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hadrian's_Villa>

(3) Seindal, Rene "Hadrian's Villa. Luxurious imperial villa from the first century CE". 2004, 19 Oct 2004<http://sights.seindal.dk/sight/901_Hadrians_Villa.html>.

(4) MacDonald, William Lloyd and Pinto, John A. "Hadrian's villa and its legacy", New Haven : Yale University Press, 1995

(5) Franceschini, Marina De "Brief History of the Villa and of the excavations", Soprintendenza Archeologica del Lazio, 2005 <http://www.villa-adriana.net/>

(6) Adembri, Benedetta, "Hadrian's Villa", Martellago (Venice): Mondadori Electa S.p.A. , 2005